You are currently browsing the monthly archive for May 2007.

Carol Vogel’s written and video reports (New York Times) on Sigmar Polke’s preparations for the upcoming Biennale have me longing, deeply longing, to see this new body of work, “The Axis of Time.” (One painting from that series is posted on Slow Painting.) Vogel visited him in his Cologne atelier and feasted on a studio overflowing with books, images, objects, materials–some of them edgy and toxic–that continue to inspire and inform Polke’s amazing body of art. His work is wide ranging, even more so than Richter’s. Not only is he a master of mystically beautiful surfaces and juxtaposed imagery, he uses pointilistic dotting like a leitmotif throughout his work. I have lost my breath several times in front of a Polke. He is a modern day alchemist to be sure.

Vogel’s reporting included some wonderful comments by Polke about his materials and the effects he is striving for. Here is an excerpt:

Mr. Polke returned to painting in earnest in the 1980s, exploring new materials and pigments so voraciously that his studio became an alchemist’s playground. He began experimenting with toxic substances, he said, because store-bought pigments often lacked the brilliant hues that he craved. He has used everything from arsenic and jade to azurite, turquoise, malachite, cinnabar and beeswax. He even extracted mucus from a snail and subjected it to light and oxygen to produce a vivid purple, in much the way the ancient Mycenaeans, Greeks and Romans created dye for their rulers’ robes.

In “Lump of Gold” (1982), he smeared arsenic directly on the canvas. Implicit was the notion that physical materials are as potent as the image itself. “He likes the idea that paintings can provide more than visual stimulation,” Mr. VeneKlasen said. “Large amounts of arsenic can kill, while small portions can heal.”

“Alabaster has its own mystical history, people can understand it, but tourmaline is more sophisticated, glowing,” he said, pointing to a tourmaline sample, with its prismatic crystals. “It forms nice patterns, it’s not as ordinary. This is all about the idea of the most holy things.”

Recently he has focused on how light changes the texture and colors of the canvases. “Light is a metaphoric thing,” taking on diverse emotional meanings, he explained over cups of tea in his living area. “There is green light and red light. Then there is black light, which is mostly danger.”

“I am trying to create another light, one that comes from reflection,” he said of the glow that emanates from the layers on his canvases. “Like celestial light, it gives the indication of new, supernatural things.” Some of the works will resemble golden landscapes, and another a sunrise. Their dusky texture is intended to induce a sort of drowsiness in the viewer.

What a wonderful pondering on the other dimensions of light! And his description of creating another light source–one that comes from reflection and from the layers of the painting–is as close a description as I can get to on what I am working through in my work as well.

I saw an excellent production of Harold Pinter’s 1975 play, No Man’s Land, at American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge last night. While I respect Pinter’s larger than life influence on the theatre communities of both the US and the UK, he is not one of my favorite playwrights. My actor friend Kevin claims that Pinter is great to perform–his work is tight and a good actor just loves to give it a go. That makes sense to me, particularly after having seen two elderly masters bring this piece to its knees. Hats off to Paul Benedict and Max Wright. They were jaw dropping good.

From the program notes, here’s prickly Pinter giving himself some elbow room:

Someone asked me what my work was “about.” I replied with no thought at all and merely to frustrate this line of inquiry: “The weasel under the cocktail cabinet.” That was a great mistake. Over the years I have seen that remark quoted in a number of learned columns. It has now seemingly acquired a profound significance, and is seen to be a highly relevant and meaningful observation about my work. But for me the remark meant precisely nothing…What am I writing about? Not the weasel under the cocktail cabinet…I can sum up none of my plays. I can describe none of them, except to say: “That is what happened. That is what they said. That is what they did.”

Painted images from Chauvet Cave

Horses drawn by Nadia at 3 years, 5 months

Nicholas Humphrey, author and expert on the evolution of consciousness, wrote a paper several years ago comparing the cave art at Chauvet Cave with work produced by Nadia, an autistic child who lived in England, who was not able to employ verbal language as a small child. Drawings that she did when she was very young (in some cases only 3 years old) have similarities with the cave art that are undeniable–the naturalism of individual animals (their portrayal is not stereotyped or iconized,) use of linear contours, the overlapping of forms, an overemphasis on salient parts (like feet and faces,) among others.

Humphrey disagrees with the contention of many scholars that cave art reveals a capacity for symbolic thought and sophisticated visual representation. His position is quite different:

The paintings and engravings must surely strike anyone as wondrous. Still, I draw attention here to evidence that suggests that the miracle they represent may not be at all of a kind most people think. Indeed this evidence suggests the very opposite: that the makers of these works of art may actually have had distinctly pre-modern minds, have been little given to symbolic thought, have no great interest in communication and have been essentially self-taught and untrained. Cave art, so far from being the sign of a new order of mentality, may perhaps better be thought the swan-song of the old.

With so little evidence to build on, experts will continue to disagree on the nature of some of the most startlingly beautiful art ever made. Lines are being drawn regarding the claim that the art is a shamanic, out of body expression, and another theory posits that the cave art was painted by women. Juxtaposing Nadia’s early drawings with representative cave art is a powerful visual case for Humphrey’s assertions, one that is strengthened by the fact that Nadia’s artistic proclivities disappeared when she learned to talk and was able to converse with others.

The paper, Cave Art, Autism, and the Evolution of the Human Mind is full of images and can be downloaded as a PDF file if you are interested by going to Cogprints.

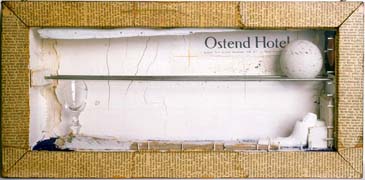

Cornell could take you into the universe in the space of a thimble.

Robert Lehrman, Cornell collector

An extensive Joseph Cornell retrospective is currently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem Massachusetts. Seeing the range, depth and subtlety of his work left me speechless. I spent hours in the show but will have to go back again. There’s just too much to comprehend in one visit.

Cornell is one of those artists that other artists revere. How can you not? His work is quirky, one-of-kind, deeply memorable. He creates visual and visceral tensions–between the sensual and the restrained, the obvious and the subliminal, the logical and the irrational. Not only does he tap into our visual receptivity, but his work also seems wired directly into the word-based arts as well. The artist that I would consider closest to his sensibilities is Emily Dickinson. It seems so right that he was moved by her work and did a number of pieces in response to her poetry.

The flip side of that Cornell verbal/visual relationship is the number of writers who have been inspired by his work. The Cornell writer connection includes an entire volume of poetry by Charles Simic (a personal favorite of mine) and A Convergence of Birds: Original Fiction and Poetry Inspired by Joseph Cornell , an anthology assembled by Jonathan Safer Foer while he was still a student at Princeton. Foer solicited work from writers in response to Cornell’s bird boxes and was able to entice the likes of Diane Ackerman, Rick Moody, Joyce Carol Oates and Robert Pinsky to participate.

Because of a strong cultural proclivity to “explain” artistic output through careful examination and analysis of the personal life of a maker (Cornell’s preferred term,) his was an oddball life that makes for easy pickings. (“how often have/the/doting/fingers of/prurient philosophers pinched/and/poked/thee.”) And there may be some value in holding his biography in close proximity to the work he produced, since both are far from mainstream. There are Dickinsonian similarities in the cloistered life he lived out on Utopia Parkway with his mother and disabled brother. The loneliness and yearning that sits like a layer of dust on Dickinson’s poetry is tangible in Cornell’s work as well.

Biographical material aside, the magic happens for me when I allow these pieces to speak on their own terms. Cornell was a man with a passionate interest in so many areas of study–astronomy, maps, physics, art history, mechanics, nostalgia, mysticism, movie stars (he moves high brow to low brow without losing a beat,) among others. He brings an eclecticism to his assemblages that is intelligent, provocative and intentional. Surrealistic art can at times feel forced and catch-as-catch-can, but there is nothing random about Joseph Cornell’s work.

The show in Salem runs through August 19th. Then good news for my friends in the Bay Area–the show is coming to San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art in October.

Many of you know that in addition to writing this blog, I maintain another blog called Slow Painting that filters through websites, publications and blogs for compelling excerpts. Slow Painting is a customized assemblage of art-related news, ideas and concepts as defined by my sensibilities.

Every so often a Slow Painting find is so provocative that it migrates over into this more personal space as well. Two recent postings on Slow Painting have filled my attention this week, one of them being the work of photographer Lynn Davis.

In a review of Davis’ current show, the photographer is quoted as saying:

What I’m looking for are sites that evoke a feeling of inner peacefulness, some quality of contemplation. I don’t always get it, and I don’t always translate it, but I certainly know when the feeling comes over me, and that’s what keeps me going.

As a affirmation of her success in achieving that goal, her work is being featured at the Rubin Museum of Art, a museum dedicated to promoting the art and culture of the Himalayas. Even though her work does not fit in with that directive per se, the museum staff could see how closely aligned her aesthetic goals are with the spirit and intention of the museum.

I have been a fan of Davis’ photographs for many years. Her images, particularly those experienced full scale, capture the essence of embodiment–that ineffable sense that all things are part of a living, breathing cohesiveness that we give many names to but is in fact one immense entity. Touching into that is the highest achievement I can imagine for someone working in the visual realm.

For those of you near New York, her work can be seen at the Rubin Museum through July 16. A catalog will be available in August.

One of my favorite bloggers posted the rules he gives to his writing students. These excellent guidelines for writers (and readers) are applicable as well to those of us who work in the visual arts.

I have extracted from his posting below, but you can read the entire piece on his blog, Joe Felso: Ruminations.

I encourage my students to formulate internal lists of what they value in writing, what they think works and doesn’t, what helps and doesn’t. I tell them that being so deliberate about your writing “rules” assists you in another way— it contributes to your evolution by moving you up to new and better rules.

Here are what I would consider my personal big three:

1. Robert Frost said, “No discovery for the writer, no discovery for the reader.” My own version of that idea comes from one of my teachers in graduate school, Susan Cheever. Susan told me that English instructors teach writing exactly wrong. They tell students to pick topics they like, subjects they know. They ought to be urging them, she said, to write about what troubles, confuses, frightens, or otherwise eludes them. To write well, you must gamble. You should never, never, never know entirely what you want to say.

By the way, while I try to live by this rule myself, it’s had mixed results as advice. The chief danger is that you throw filaments hoping something will catch and end up “noodling” or—I’m being discreet here—playing “verbal solitaire.”

2. Good writing breathes or, put more concretely, it expands and contracts in its attention to the subject. Working close to the trees, in tiny, precise, and ample detail, begets an impulse to fly high and see the whole forest. Every broad statement demands a return to actual stuff broad statements rest upon. A writer who works particularly well in this way is Joan Didion. Her essays are neither minutiae interrupted by wisdom nor wisdom interrupted by minutiae. They are the un (see rule #1) holy marriage of both. They tack back and forth, making the most of the lightest breath as they beat against the current.

Note: William Carlos Williams’ “No ideas but in things” seems a violation of this rule but really isn’t. Williams acknowledged ideas and things were indivisible; one without the other is mute.

3. Break a rule everyday. Some student writers glom onto form like the last life jacket. They’d like adherence to be the greatest measure of merit. As they gain experience as readers however, they come to appreciate artful violations. I like the asymmetrical paragraph, clichés that jump ship rope, and sentences that refuse.

Rhyme is okay with me, but I love the way Dickinson drops it, the way Gerard Manly Hopkins hides it, the way Eliot juggles it inside lines, the way Richard Wilbur transmutes it.

It helps to know what readers expect, but better to know what they don’t. Behind all three rules lies movement, misdirection, and surprise.

Nicole Long, poet and friend, sent me this quote from Henri Nouwen:

A few times in my life I had the seemingly strange sensation that I felt closer to my friends in their absence than in their presence. When they were gone, I had a strong desire to meet them again but I could not avoid a certain emotion of disappointment when the meeting was realized. Our physical presence to each other prevented us from a full encounter. As if we sensed that we were more for each other than we could express. As if our individual concrete characters started functioning as a wall behind which we kept our deepest personal selves hidden. The distance created by a temporary absence helped me to see beyond their characters and revealed to me their greatness and beauty as persons which formed the basis of our love.

I know what Nouwen is describing, and I have experienced these feelings at various times in my life. Why the physical domain impacts certain relationships more than others, I do not know. And as the availability of other modes of interaction that do not include a physical presence–phone and online for example–but can deliver their own version of intimacy, the “in the flesh” version of human interaction is morphing as well.

This is a more complex issue than the often voiced concern about people spending too much time online. Nouwen was a priest (often compared with Thomas Merton and Teilard de Chardin) who wrote a great deal about solitude as well as the concomitant longing and need for community. He has been described as a man who had many friends but constantly struggled with a profound sense of loneliness. And while this quote could be viewed as a psychological indicator of his personal struggle with intimacy, it hits on something much more profound.

Walls that protect our “deepest personal selves” appear all the time, and what works to get past them has often surprised me. Like most people, I have intensely personal relationships with people I connect with online, people I have never met in the flesh. An emotional intimacy emerges in those online interactions that would take much longer to achieve in person. And while some of those relationships may be able to transmogrify into full bodied friendships, others may not. But having these options for connection, disembodied though they may be, is like finding a whole new wing of your house you didn’t know was there.

Beginners

How could we tire of hope

So much is in bud now?

We have only begun to imagine justice and mercy,

Only begun to envision how it might be to

Live as siblings.

We have only begun to know the power that is in us.

So much is unfolding that must complete its gesture.

So much is in bud.

Denise Levertov

I can’t move on, not just yet…Still thinking about Tom Stoppard’s trilogy, Coast of Utopia, and about Isaiah Berlin’s insightful Russian Thinkers, the book that launched Stoppard’s interest in writing about this historical period in the first place. Here is another quote from Aileen Kelly’s excellent introduction to Berlin’s book, a quote that is so apropos to our current circumstances, politically and culturally:

Berlin suggests that pluralist visions of the world are frequently the product of historical claustrophobia, during periods of intellectual and social stagnation, when a sense of the intolerable cramping of human faculties by the demand for conformity generates a demand for “more light,” an extension of the areas of individual responsibility and spontaneous action. But, as the dominance of monistic doctrines throughout history shows, men are much more prone to agoraphobia: and at moments of historical crisis, when the necessity of choice generates fears and neuroses, men are eager to trade the doubts and agonies of moral responsibility for determinist visions, conservative or radical, which give them “the peace of imprisonment, a contented security, a sense of having at last found one’s proper place in the cosmos.” He points out that the craving for certainties has never been stronger than at the present time; and his [writings] are a powerful warning of the need to discern, through a deepening of moral perceptions–a “complex vision” of the world–the cardinal fallacies on which such certainties rest.

In addition to that larger arc of America’s current political mindset, this quote also addresses the predicament of life on a personal level as well. My good friend Susana Jacobson poses the following question to her students to help them determine if the life of a fine artist was for them: Can you imagine living your entire life in uncertainty? That’s what being an artist is: You’ll never know if your work is any good, you’ll never get the kind of feedback that other professions provide. So if certainty is important to you, find a different path.