You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Art/Language’ category.

Being at home in a layered reality…The view through the rooms in Stephanie’s magical Rockport home

I’ve confessed here before to the paradox at the core of my art making and blog writing persona: I don’t believe art can be parsed and analyzed in language the way other topics can be. But there are words and languaged explorations that inhabit the borders of that non-languaged land and are of interest and value. This blog is about the content that lives in that liminal zone, bordering the border and at home along that edge.

Laurie Fendrich is a blogger on the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Brainstorm site and has written about the “deafening silence” she encounters whenever she writes about art. When the topic is politics, the switchboard lights up and everyone wants to log in on their opinion. Why so little commentary when the topic is art?

A lot of people can’t understand how art of any kind conveys meaning. At its best, it seems to sit there, or hang there, waiting to be contemplated for some sort of aesthetic pleasure. What else is there to say about it? At the same time, many are terribly intimidated by art—especially modern and contemporary art. They find they don’t like it, but worse, they’re annoyed that they don’t “get” it. It seems as if it’s part of a club they aren’t allowed to join. Tethered as they are to their preconceived ideas about what a painting should do (it should be beautiful, or at least good-looking, or it should tell a story, or be noble, or be about flowers, or the Bible), a lot of people think modern and contemporary art is nothing but one enormous joke. Since this is hardly the kind of thing sophisticated people want to admit, they prefer to keep quiet about the subject.

But Fendrich goes on to point out another aspect that impacts public interaction with the visual arts. This is one that particularly resonates with my views:

For aesthetic taste to broaden generally requires a lot of serious, direct experience with art—lots of time hanging around museums, galleries and artists’ studios. It helps to read about art, or listen and talk to people who love it, or are at least involved in it. Yet even then, and even among the educated elite, only a relatively small group of people do any of these things on any kind of regular basis. People in the humanities (where you’d think you’d find a lot of people who pay attention to art) are frequently just as alienated, flummoxed or indifferent to art as the masses that are obsessed with pop culture. The stock and trade of academics is words, not images, and for all their ability to analyze culture, academics are mostly blissfully ignorant of what it takes to make something that becomes a part of culture—a work of art, or a product of scientific inquiry and experiment. For all their study of ideas and actions (artistic or otherwise), and all their inventing of explanations and theories about what creative people do, in both art and science, they rarely ever try their hands at creative work.

On the consistently interesting blog Real Clear Arts, Judith H. Dobrzynski has written a thoughtful response to the difference between talking about politics and talking about art:

Fendrich almost makes that reticence a virtue as she dissects why everyone feels so free and almost obligated to talk about politics: “For most of us, talking about politics has become merely another means of self-expression — another way to yell (if we’re bullies), rant (if we’re full of tension), sound reasonable (if we’re nice people).”

But that has consequences: “People eagerly opine about politics because talking about politics today has deteriorated into nothing but a game of chatter–a way of responding to the unsettling modern world that seems so devoid of much that’s beautiful or good.”

So cheer up, art-lovers. Would you rather have a lot of people blather on and on about something, even when they don’t know much, or remain quiet because they don’t know much?

More specific to my particular concerns, a comment on Dobrzynski’s blog left by “Joan” captures many of my feelings with this thoughtful note:

The only language that really touches the purposes or heart of art is poetry, not analysis. Why? Because a work of art isn’t a response to a rational question. I don’t mean by that the arts are irrational. If a work of art does emerge from thinking, it is born from the place where thinking comes to a sort of intellectual dead end past which it can’t verbally go. Is America so materialistic it has forgotten that there is meaning apart from rational thought or the work and progress of science and technology?…The heart of art is non-verbal, experiential, practical, and non-commercial. Why blab about it- unless you’re an art student or artist talking to other artists, deeply involved in discovery about what it is and how it is, that you are doing what you are doing??

In his essay “Light and Space and Darkness: Taking Painting Full Circle in the Wireless World” (published in Darren Waterston: Representing the Invisible) David Pagel had me at hello. He’s a stylist of the finest art writing order, and he brings the inchoate beauty of Waterson’s work as close to language as I can imagine them getting.

A few samples follow.

***

On the loss of space and the possibility of splendid isolation:

Space is not what it used to be. In the 1960s, the most prominent feature of the cosmos was the infinite possibility of silent emptiness—a vastness so profound, inhuman, and endless that it naturally attracted the best and the brightest minds to take off on futuristic, quasi-mythological quests to discover its secrets by traversing the mind-blowing distances through which nothing but light—and the occasional meteorite—had traveled. Today, emptiness, silence, and even distance are in short supply. More people are packed into bigger, more cacophonous urban sprawls than ever before. A historically unprecedented level of visual stimulation constantly bombards us, diminishing attention spans as it fuels the desire for instantaneous gratification. And the wide-open silences that once left individuals free to follow their imaginations to roam aimlessly have been replaced by the incessant, omnipresent, invisibly transmitted communications made possible by a plethora of wireless technology…Today, the romance with silent emptiness is all but over, both in the visual arts and the popular imagination. The general public’s fascination with travel through deep space has waned, if not disappeared altogether.

***

On Waterston’s work:

The beauty of Waterston’s work resides in its fluidity, its capacity to dissolve hard-line distinctions between the substance of material reality and the power of the imagination. His paintings are timely because they move freely between the inner, invisible world of memory and fantasy and desire, and the outer, visible world of shared public space and recognizable representations. They are graceful and gracious because they fuse the look, feel, and giddy tempo of advanced digital technology with the slowly unfolding pleasures of techniques and procedures associated with Renaissance painting, when our modernity was just beginning, when tie moved more slowly and pateince was still a virtue, when painstakingly applied glazes were layered atop one another to create visually resplendent surfaces filled with more atmosphere and space than their literal dimensions and physical depths seemed capable of containing.

***

On artistic point of view:

None of Waterston’s paintings focuses a viewer’s attention on his self. None strives to express his inner sentiments. And none is even loosely autobiographical. The radical individualism that is often thought of as the raison d’être of art-making, especially expressive, abstract painting, plays an impressively unimportant role in Waterston’s works, which uniformly dissolve the artist’s self into anonymous, organic processes. This humble selflessness is a form of generosity, a means to leave viewers ample room to maneuver, interpreting and engaging the paintings in whatever manner best suits us.

______

For more information about Darren Waterston and his work, his website is here.

David Pagel is an art critic who writes regularly for the Los Angeles Times. He is an adjunct curator at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton, NY.

The intensity of the last week and the death of two friends in such a short period of time have been a strong wind sailing me straight into a setting sun. I haven’t been to my studio for over a week. In spite of deadlines for upcoming shows I am allowing my hands to lie fallow, to nest the quietude of my grief. And while my sorrow has silenced my expression, I am being nested by a husband who knows how to nurture my sadness. Painting and sex are the two great revitalizers of my life, and I am at my finest when both are in flow. I’ll be back in the studio soon, but thank god for both of these life-giving gestures.

This passage from Seamus Heaney’s collection of prose, Finders Keepers, spoke deeply to me. I want to share a few passages with my poetry-loving readers from his essay, Feeling Into Words.

I intend to retrace some paths into what William Wordsworth called in the ‘The Prelude’ “the hiding places”:

The hiding-places of my power

Seem open; I approach, and then they close;

I see by glimpses now; when age comes on,

May scarcely see at all, and I would give,

While yet we may, as far as words can give,

A substance and a life to what I feel:

I would enshrine the spirit of the past

For future restoration.

Implicit in these lines is a view of poetry which I think is implicit in the few poems I have written that give me any right to speak: poetry as divination, poetry as revelation of the self to the self, as restoration of the culture to itself; poems as elements of continuity, with the aura and authenticity of archaeological finds, where the buried shard has an importance that is not diminished by the importance of the buried city; poetry as a dig, a dig for finds that end up being plants.

Digging, one of Heaney’s most famous poems was also the first poem where he believed he had been able to get his feelings into words. Or more accurately, get his “feel” into words.

This was the first place where I felt I had done more than make an arrangement of words: I felt that I had let down a shaft into real life.

Tom Stoppard and Conor McPherson each hold pole positions in their respective areas of expertise—Stoppard is the master of idea-driven theater and McPherson is the feelings first guy. In the production of Shining City currently playing in Boston, McPherson’s characters carve out a reality driven by the way it feels inside rather than some rational, linear external version of the story. McPherson has an ear for language of the human heart the way Stoppard has a mind that can constellate powerful ideas into drama.

Here’s a brief overview from critic Albert Williams:

When Shining City made its Broadway debut in 2006, its author, Irish playwright Conor McPherson, candidly discussed his painful journey toward sobriety after years of alcohol abuse—an addiction that nearly cost him his life in 2001, when at the age of 29 he was hospitalized with pancreatitis. “In going to therapists, I realized how many crazy people are in that job,” McPherson told a New York Times writer. “To want to do a job like that, you have to be very attracted to dysfunction.”

The same can be said of most playwrights. And McPherson is a very good playwright. In Shining City—now receiving its beautifully acted Chicago premiere under the direction of Robert Falls, who also staged the New York production—McPherson fuses extraordinary skill at shaping language with an aching awareness of the difficulties of communicating. His characters are remarkably real, and the psychological and spiritual journeys they take are readily recognizable; McPherson has clearly invested himself in each of them.

When McPherson wrote about Samuel Beckett, theater god and fellow Irishman, he holds up a mirror for his own work’s power:

Each one [of Beckett’s plays] is a beautifully honed, determined, focused world unto itself…I believe that his plays will continue to echo through time because he managed to articulate a feeling as opposed to an idea. And that feeling is the unique human predicament of being alive and conscious. Of course, it’s a very complicated feeling (and it’s a complicated idea), but he makes it look simple because his great genius, along with his incomparable literary power, was the precision and clarity he brought to bear in depicting the human condition itself.

“I’ve always had an existential darkness,” McPherson says…”An awareness of the predicament of being alive. We’re alive in this cold and mysterious universe, and we’re only very small. That seems to me to be a stunning predicament.”

It IS a stunning predicament. But when McPherson crafts characters who can speak with such strange and sometimes mad clarity, I am reassured to know that angst is not a solitary journey.

I have had a small book titled Chromophobia on my shelf since it was published in 2000. After dipping in and out of it over the last few years and being delighted and intrigued, I finally read it from stem to stern. It is a terrific, terrific book.

The author, David Batchelor, is a sculptor whose work is focused on color (or, because he is British, colour.) He also happens to be an insightful and articulate thinker, and this small book has been feeding my thinking for days.

Batchelor’s basic premise is this: “It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that, in the West, since Antiquity, colour has been systematically marginalized, reviled, diminished and degraded…As with all prejudices, its manifest form, its loathing, masks a fear: a fear of contamination and corruption by something that is unknown or appears unknowable.” Drawing from sources that range from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, and the philosophic writings of Aristotle, Charles Blanc, Le Corbusier and Roland Barthes among others, the book unmasks our cultural discomfort with colour.

In the process of this uncovering, Batchelor has assembled some memorable references to art and colour. Here’s a few I found particularly provocative:

The poet Joachim Gasquet, reporting some remarks made by Cezanne about looking at painting:

Shut your eyes, wait, think of nothing. Now, open them…One sees nothing but a great coloured undulation. What then? An irradiation and glory of colour. This is what a picture should give us…an abyss in which the eye is lost, a secret germination, a coloured state of grace…Lose consciousness. Descend with the painter into the dim tangled roots of things, and rise again from them in colours, be steeped in the light of them.

***

Cezanne, it has been argued, subscribed to the idea that a new-born child lives in a world of naive vision where sensations are unmediated and uncorrupted by the ‘veil of…interpretation.’ The work of the painter was to observe nature as it was beneath this veil, to imagine the world as it was before it had been converted into a network of concepts and objects. This world for Cezanne, was ‘patches of colour’; thus ‘to paint is to register one’s sensations of colour.’

***

Gustave Moreau: ‘Note one thing well: you must think through colour, have imagination in it. If you don’t have imagination, your colour will never be beautiful. Colour must be thought, imagined, dreamed.”

So much more to share from this slender volume. I will do so in upcoming posts.

After several days in California, I’m readjusting to the stubbornness of a winter overlord who won’t give up New England. Succession planning? We’re working on that. Spring is off stage, bedecked in faille, fluttering her white and pink organzas, just waiting for an entrance cue.

I had some memorable moments last week, both indoors as well as out. One morning was spent at the Gilbert & George exhibit at the De Young Museum. These two have made themselves into art icons over the last thirty years with their provocative poises, proddings, posturings, promulgations. Even though I have not ever been what I would term a G&G advocate, their campy pranks aren’t just empty suit stunts and theatrics. There is more going on than that.

For example, the following statements by the artists were posted at the beginning of the exhibit:

ART FOR ALL

We want Our Art to speak across the barriers of knowledge directly to People about their Life and not about their knowledge of art. The 20th century has been cursed with an art that cannot be understood. The decadent artists stand for themselves and their chosen few, laughing and dismissing the normal outsider. We say that puzzling, obscure and form-obsessed art is decadent and a cruel denial of the Life of People.

PROGRESS THROUGH FRIENDSHIP

Our Art is the friendship between the viewer and our pictures. Each picture speaks of a “Particular View“ which the viewer may consider in the light of his own life. The true function of Art is to bring about new understanding, progress and advancement. Every single person on Earth agrees that there is room for improvement.

LANGUAGE FOR MEANING

We invented and we are constantly developing our own visual language. We want the most accessible modern form with which to create the most modern speaking visual pictures of our time. The art-material must be subservient to the meaning and purpose of the picture. Our reason for making pictures is to change people and not to congratulate them on being how they are.

THE LIFE FORCES

True Art comes from three main life-forces. They are: –

THE HEAD

THE SOUL

and THE SEX

In our life these forces are shaking and moving themselves into everchanging different arrangements. Each one of our pictures is a frozen representation of one of these “arrangements“.

THE WHOLE

When a human-being gets up in the morning and decides what to do and where to go he is finding his reason or excuse to continue living. We as artists have only that to do. We want to learn to respect and honour “the whole“. The content of mankind is our subject and our inspiration. We stand each day for good traditions and necessary changes. We want to find and accept all the good and bad in ourselves. Civilisation has always depended for advancement on the “giving person“. We want to spill our blood, brains and seed in our life-search for new meanings and purpose to give to life.

Unfortunately saying doesn’t make it so…I didn’t find this exhibit of large format images to be any more accessible to the average viewer than most other contemporary work. There’s definitely an essential tension between these populist, anti-art world sentiments and the fact that G&G are driving their luxury car down the center lane of the Art World Circus Parkway, busily exhibiting their work in museums everywhere and merchandising a boatload of posters and printed ties.

But the sentiments expressed in these words, idealistic and naive as they may read when viewed in the hard-edged context of contemporary museum scale art, mean something to me. While I don’t want to flatten the complexity of the tangle of issues that exist in contemporary art dialogue today by promoting a bipartisan view of Art World vs Anti-Art World, it might be useful to make a few categorical distinctions. Doing so has been useful to me.

Here’s one set of demarcations that I have been road testing, and it seems to be holding together. Sally Reed, artist and smart friend, has borrowed traditional literary forms, epic and lyric, and applied them to the making of art.

Epic art, says Sally, deals with large arc issues like politics, philosophy, cerebral calibrations, identity and does so through installations in public spaces like art museums and international art fairs. It is often built on a strong narrative armature, with a heavy storytelling and/or content orientation.

Lyric art is more human scaled. Personal. Demanding a relationship with the viewer on an intimate level. This is art that usually exists outside of narrative, outside of time.

I make work that would be classified as lyric. But I have been amazed and moved by both types. Most of what gets written about and discussed however is epic. Advocacy for art that is intended to incite the intensity of a full body experience is hard to find.

More from Sally Reed:

No, I am not “telling a story” — for me it’s more like (how’s this for grandiosity?) creating a world. Or more modestly, creating a place, a “chamber.” When a piece is finished, it seems I am ready to invite people in. Or at least their gaze, their thoughts and feelings.

My problem with narrative is that it often is sequential and always takes place in time. I feel that when I am making art, when I am at my best, it takes place outside of time, as a dream does. For me, the experience of making (when I am in the flow) or experiencing art, is outside of time. I think this might be why many narrative based visual pieces that I like initially can bore me on a second or third viewing. And also why certain masterpieces are endlessly fascinating; there’s always a new way to approach, a new way to experience, to sort of “unfold” all the wonders with which they are packed.

There is more to say on many of these themes, which I will continue to explore going forward.

What is it that Tom Stoppard does that moves me so deeply? Rock ‘n’ Roll was as intoxicating an experience as Coast of Utopia had been the year before. In many ways it is a continuation of many of the same themes, just brought forward 100 years and closer to home. (The play takes place in England and what was once Czechoslovakia, the bloodlines of Stoppard’s own identity.) We are still struggling with how history unfolds, how any one person can stand up, with honor, to the inexorable thrust of politics, of grand scale human folly, of historical precedence replaying itself over and over again, of disastrous conceits and misfired intentions.

In both Rock ‘n’ Roll and Coast of Utopia, Stoppard arcs his narrative out over many years and several generations. His voice does not speak to the concerns of his particular cohort group. Rather he traces the fractal pattern of how ideas grow, from what is frequently an inauspicious and unintended germination to historic unfoldings that explode with little regard for extenuating circumstances like truthfulness, appropriateness, or the achievement of any modicum of long term human benefit. The threads and leitmotifs in these plays are complex, provocative and interconnected, yet they are not delivered with anything approaching resolution. Stoppard poses profound questions about human existence that do not have answers. Intimations and flashes of possible resolutions come and go, but those moments are fleeting, a glinting parsec vision of what might have been.

An unforgettable experience.

Here is an excerpt from a review by Neal Ascherson of the Guardian, written when the play first opened in London in 2006:

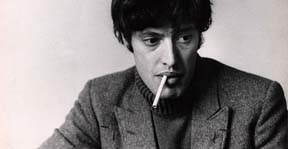

Tom Stoppard in 1967

(Photo: Jane Brown)

“Rock ‘n’ Roll” is a subtle, complex play about ways to resist ‘systems’ and preserve what is human. At its core is a succession of arguments between two Czech friends, Jan (who holds some of Kundera’s attitudes) and Ferda (who more clearly represents Havel, and borrows lines from some of Havel’s famous utterances). Jan, forced to work as a kitchen porter, at first despises Ferda’s petitions against arrests and censorship as the self-indulgence of an intellectual clique. A devout rock enthusiast, he sees the persecuted rock band the Plastic People of the Universe (who actually existed) as the essence of freedom because they simply don’t care about anything but the music. They baffle the thought police because ‘they’re not heretics. They’re pagans’.

Ferda at first dismisses the Plastic People as long-haired escapists who have nothing to do with the real struggle. But later, when they are arrested and imprisoned after an absurd trial, he comes to understand that the heretics and the pagans are inseparable allies.

Leaving the band’s real-life trial, Havel famously said that ‘from now on, being careful seems so petty’. Soon afterwards a few hundred brave men and women signed ‘Charter 77’, the declaration of rights and liberties which earned them prison sentences and suffocating surveillance but which was read around the world.

Stoppard is fascinated by the Plastic People, by the idea that the most devastating response to tyranny might be the simple wish to be left alone. In Prague he met and talked to Ivan Jirous, their founder, whose long hair enraged the authorities. ‘I always loved rock’n’roll,’ Stoppard says. ‘And what was so intriguing about the Plastic People was that they never set out to be symbols of resistance, although the outside world thought of them that way. They said: “People never write about our music!” In the West, rock bands liked to be thought of for their protest, rather than their music. But Jirous didn’t try to turn the Plastic People into anything; he just saw that they were saying, “We don’t care, leave us alone!” Jirous insisted that they were actually better off than musicians in the West because there was no seduction going on. There was nothing the regime wanted from them, and nothing they wanted from the regime.’

There is dissent which wants to substitute one system for another. And there is dissent which simply says: Get off our back, scrap all the guidelines and controls, and humanity will reassert itself.

Patiently, Stoppard explained to me how historic disputes between Kundera and Havel were reflected in the play. Kundera, in the first confused year after the invasion, had hoped that the experiment could still continue, working out a society in which uncensored freedom could co-exist with a socialist state, a new form of socialism which still needed to be devised. ‘Havel said that it wasn’t a question of making new systems. “Constructing” a free press was like inventing the wheel. You don’t have to invent a free society because such a society is the norm – it’s normal.’

I asked if this notion of freedom as ‘normal’ and ‘natural’, something which doesn’t need designing, wasn’t close to the anarchist vision But this was not what he meant, it seemed. Stoppard’s trust that ‘people’ will behave well when left on their own has its common-sense limits. In “Salvage”, the third play in the “Utopia” trilogy, Stoppard makes Herzen puncture the exuberant anarchist Mikhail Bakunin in a needle-sharp exchange:

Bakunin: ‘Left to themselves, people are noble, generous, uncorrupted, they’d create a completely new kind of society if only people weren’t so blind, stupid and selfish.’

Herzen: ‘Is that the same people or different people?’

Ever since it was first published in 1998, Uncontrollable Beauty: Toward a New Aesthetics, edited by Bill Beckley with David Shapiro has been my primary text. This collection of essays brings together the thinking of artists and critics on the greatly misunderstood (and much maligned) topic of beauty.

Uncontrollable Beauty embodies many of the reasons why I began blogging in the first place. It speaks to what was not being paid attention to, written about, dialogued, analyzed or acknowledged in the contemporary world of art.

Here are some excerpts from that collection:

Agnes Martin: When I think of Art, I think of Beauty, Beauty is the mystery of Life. It is not in the eye, it is in the mind. In our minds there is awareness of perfection.

Peter Schjeldahl: ‘Beauty is Truth. Truth Beauty?’ That’s easy. Truth is a dead stop in thought before a proposition that seems to obviate further questioning, and the satisfaction it brings is beautiful.

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe: In the art world, the idea of the beautiful is always threatening to make an appearance or comeback but it tends always to be deferred.

Santayana: To feel beauty is a better thing than to understand how we come to feel it.

Louise Bourgeois: Beauty? It seems to me that beauty is an example of what the philosophers call reification, to regard an abstraction as a thing. Beauty is a series of experiences. It is not a noun. People have experiences. If they feel an intense aesthetic pleasure, they take that experience and project it into the object. They experience the idea of beauty, but beauty in and of itself does not exist. Experiences are sorts of pleasure, that invoke verbs. In fact, beauty is only a mystified expression of our own emotion.

So I was particularly delighted to add a new volume to my favored bed stand stack–another articulate defense of art that is not just cerebral, conceptual, emotionally detached and non-retinal. Ellen Dissanayake, author of Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes from and Why (which was first published in 1992!) approaches philosophical aesthetics from an unexpected point of view. She does not approach art as a scholar of visual language but as an ethologist and anthropologist. Her claim is that art is as intrinsic to human life as other observable behaviors like the proclivity to ritual, play, seeking sustenance. This tendency in us to “make special” is biological and as Dissanayake has termed it, “species-centric.” She spends several chapters of her book examining the anthropological parallels of art in other cultures, but it is her extraordinary skill at seeing through the vacuity of postmodernism in the visual arts that makes this book a terrific and reinforcing read for anyone interested in these issues.

Here is an excerpt from her preface that captures much of her basic argument:

While artists and art teachers might especially welcome a biological justification for the intrinsic importance of their vocation, everyone, particularly those who feel a loss or absence of beauty, form, meaning, value, and quality in modern life, should find this biological argument interesting and relevant. Ironically, today, words such as beauty and quality may be almost embarrassing to employ. They can sound empty or false, from their overuse in self-help and feel-good manuals, or tainted by association with now-repudiated aristocratic and elitist systems in which ordinary people were considered “common” for not having the opportunity to cultivate appreciation of these features. But the fact remains that even when we are told that “beauty” and “meaning” are socially constructed and relative terms insofar as they have been used by elites to exclude or belittle others, most of us still yearn for them. What the species-centered view contributes to our understanding of the matter is that knowledge that humans were evolved to require these things. Simply eliminating them creates a serious psychological deprivation. The fact that they are construed as relative does not make them unimportant or easily surrendered. Social systems that disdain or discount beauty, form, mystery, meaning, value and quality—whether in art or in life–are depriving their members of human requirements as fundamental as those for food, warmth, and shelter.

The Layers

I have walked through many lives,

some of them my own,

and I am not who I was,

though some principle of being

abides, from which I struggle

not to stray.

When I look behind,

as I am compelled to look

before I can gather strength

to proceed on my journey,

I see the milestones dwindling

toward the horizon

and the slow fires trailing

from the abandoned campsites,

over which scavenger angels

wheel on heavy wings.

Oh, I have made myself a tribe

out of my true affections,

and my tribe is scattered!

How shall the heart be reconciled

to its feast of losses?

In a rising wind

the manic dust of my friends,

those who fell along the way,

bitterly stings my face.

Yet I turn, I turn,

exulting somewhat,

with my will intact to go

wherever I need to go,

and every stone on the road

precious to me.

In my darkest night,

when the moon was covered

and I roamed through wreckage,

a nimbus-clouded voice

directed me:

“Live in the layers,

not on the litter.”

Though I lack the art

to decipher it,

no doubt the next chapter

in my book of transformations

is already written.

I am not done with my changes.

–Stanley Kunitz

Thank you to friend and photographer Barbara Gates for sending this poem my way.

I’m still sitting in the fragrance of the excerpted passages from the Francis Clines article that I posted earlier this week. This visual image for example has a powerful persistence for me:

For his opening classes at Harvard, Heaney usually prescribes selections from East European poets, stark verse that is hardly the language of bogus comfort, but is ”antipoetry, a kind of wiresculpture poetry,” in which he finds that ”the density of the unspoken thing is where the meaning lies.”

So, from a volume of poems by Polish poet Adam Zagajewski, here’s a journey into the wiresculptured view.

My Aunts

Always caught up in what they called

the practical side of life

(theory was for Plato),

up to their elbows in furniture, in bedding,

in cupboards and kitchen gardens,

they never neglected the lavender sachets

that turned a linen closet to a meadow.

The practical side of life,

like the Moon’s unlighted face,

didn’t lack for mysteries;

when Christmastime drew near,

life became pure praxis

and resided temporarily in hallways,

took refuge in suitcases and satchels.

And when somebody died–it happened

even in our family, alas–

my aunts, preoccupied

with death’s practical side,

forgot at last about the lavender,

whose frantic scent bloomed selflessly

beneath a heavy snow of sheets.

Don’t just do something, sit there.

And so I have, so I have,

the seasons curling around me like smoke,

Gone to the end of the earth and back without sound.

(Translated by Clare Cavanagh)